Second Sunday of Christmas, 2025. Year A. Evensong – second service readings.

Isaiah 41:21-42:4

The second half of our reading this evening from Isaiah is the first of four ‘suffering servant’ passages that are found in the second half of Isaiah.

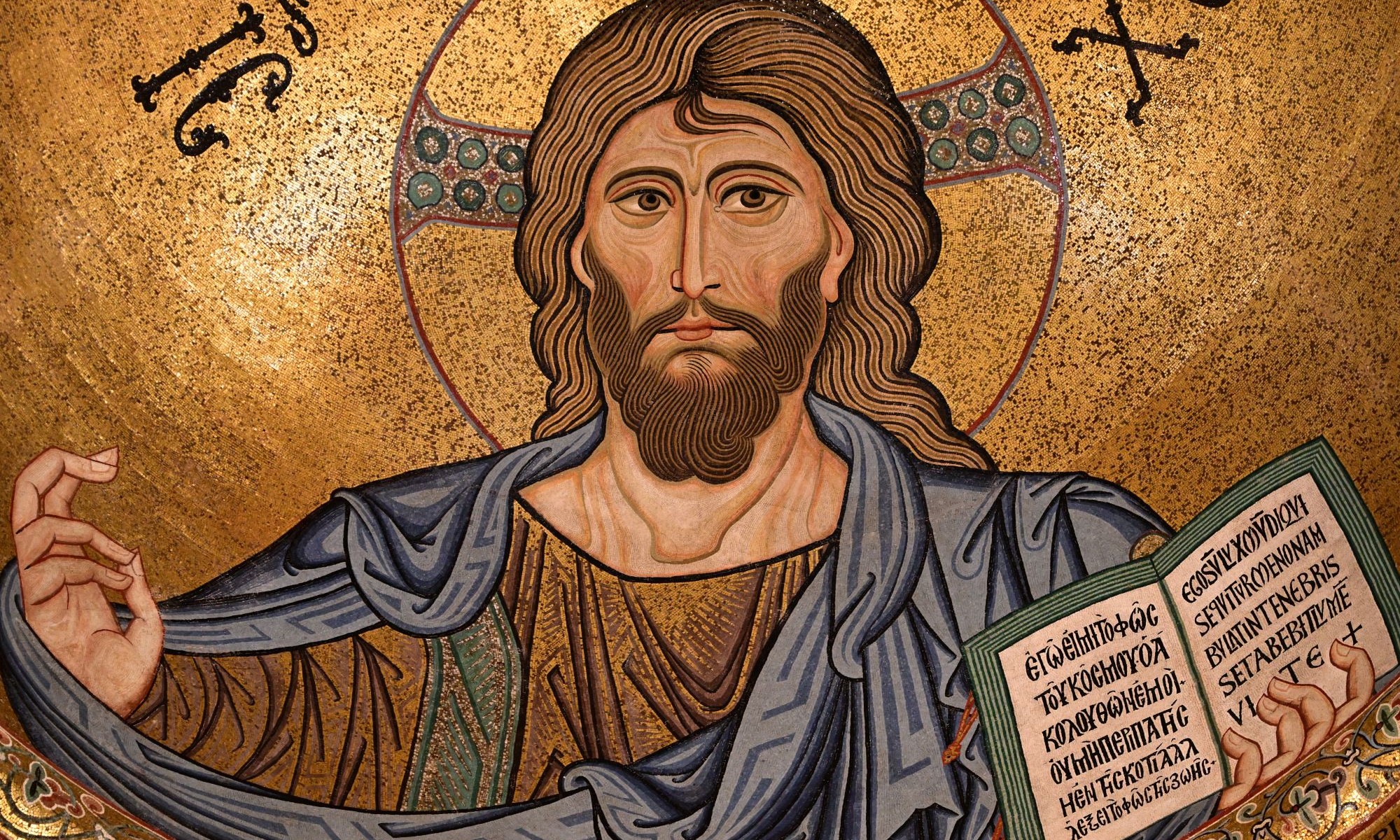

From the very earliest of Christian writers, these passages, culminating in Isaiah 52-53, have been seen as a messianic prophecy that was fulfilled by Jesus, and in his own words in the Gospels, Jesus spoke of himself in a way that made it clear to people that he was the fulfilment of these prophecies, and that he was the sort of messiah that these prophecies spoke of.

This because these visions speak of a very different sort of Messiah. The imagery develops over the four songs, and the element of suffering for which they are most notable doesn’t enter until later, but even here we are presented with a striking image of the servant.

This is not the normal covenantal restoration of Isreal that we expect. There is no overthrowing of oppressors and elevation of Zion above other nations. God will not come to crush the kings of the earth.

Instead, the servant will bring forth justice to the nations – all the nations. And how will he do it?

Not by crying out, or lifting up his voice in the street.

There will be no violence to others, even an already damaged reed will not be broken by his coming.

Instead he will faithfully bring forth justice. Faithfully, slowly, gradually, inexorably, indefatigably and continuously.

He will not be fatigued, or turn aside from his goal.

Not even, we now know, when violent hands are laid upon him. Instead, he will go faithfully to his death, but even death will have no hold over him. He will shrug off the bonds of death with his faithful obedience.

What does this mean for us?

Firstly, that we have a unique model of power and majesty set before us. God is glorified not by his dominance, or his ability to violently compel others to his will, but by his patience and faithfulness. God has established covenants and made promises, and he will always abide by those covenants.

When we set out to live our lives in the way of God as revealed in Jesus Christ, we commit ourselves to be righteous in the same way. We commit ourselves to bring justice to the nations – to each other, and to every human that we meet, not just to our own family, or community or nation, but all the nations of the earth.

We do not need to cry out or raise our voices in the street. We do not need to fight for justice. We are not called to impose justice on others. We are called to peaceful witness. The results of this will not come soon.

This is the second thing that this means for us.

We are in this for the long haul. The problems of creation are not something that we can solve by our own efforts, and they will not be solved in our lifetimes necessarily. We shouldn’t be looking for short term solutions, but rather we should be showing consistent faithfulness to God’s promises in Jesus Christ. God isn’t promising to fix creation right away – the problems run too deep for that, and we shouldn’t trust those who promise easy answers or quick fixes for anything. God will be faithful to his covenants for ever, and we need to be equally persistent in our quiet faithfulness.

Amen