4th Sunday of Advent, 2025. Year A.

The fourth Sunday of Advent is upon us already. Christmas is only 4 days away. Hopefully all of you have bought all your Christmas presents for those you love, and also for those you don’t.

The waiting is almost over, and at the same time, the waiting continues.

Advent is a time of expectation and preparation for the coming of Jesus. Not just looking back to his incarnation 2000 years ago, but also to his eschatalogical coming – the final arrival of the kingdom of God for which we are all waiting.

And there have been times over the last year where it has felt like the kingdom of God really can’t come soon enough.

The four Sundays of Lent are traditionally themed – last Sunday we considered John the Baptist, and this Sunday we consider the Virgin Mary.

But interestingly our lectionary reading for this week focuses as much on Joseph as it does on Mary. Indeed this is the passage in the bible where we learn the most about Joseph’s character and role. And it’s really not much to go on.

What do we learn about Joseph? He is righteous, at least by the standards of his time. When he discovers that Mary is already pregnant, and presumably draws the obvious conclusion, he resolves to quietly break their engagement.

And he is obedient, at least to the angel, when he is told not to take this course of action.

Obedience to God’s will is of course what we most often think of when we think of Mary as well.

Obedience to God’s will is of course something that is admirable, but that obedience shouldn’t necessarily be completely unquestioning, especially if the mediator of God’s will is something less credible than an angel.

And indeed even angels can be deceivers as well, we should remember.

I would suggest that when we usually read this passage we project a lot of our own cultural preconceptions into this passage when we think about the parallel roles of Mary and Joseph in the incarnation.

For Mary we have a habit, if we are not careful, of overemphasising her meek obedience to the will of God, and transforming that into a normative role for women of being meek and obedient in all that they do – a role that is not conditioned by the Gospel, but by our own cultural prejudices.

I was reminded of that this week reading the Church Times, and a review of the Channel 4 documentary about the John Smyth abuse.

Part of it was dwelling on the role of his wife, Anne, as both victim and unwilling participant.

A quote about her described her as “‘the perfect Christian wife’, because she never stood up to him”.

How do we end up here?

Overemphasising Mary’s obedience, and underemphasising to whom that obedience is directly given runs the risk of us falling into this cultural trap.

It has to be the foundation of us being a safe church and a Gospel-values-living-out community that obedience should never be given blindly, and trust should always be conditional and accountable.

At the same time as we are taking Mary as an ideal of submissive female obedience, we do not seem to be doing the same for Joseph.

You will, unfortunately, I think, find few authors holding up Joseph as a model for male qualities because of his submissive obedience to God’s wishes.

Despite, of course, that in this he is just foreshadowing Jesus’ own submissive obedience and faithfulness to God’s covenant when he meekly goes to his death on the cross 33 years later.

This seems a far cry from the muscular and aggressive Christianity that large parts of the church have spent the last two millenia endorsing, and which once again seems to be raising its ugly head in current events.

We carry a long burden of sin as a church.

But the response to sin is to repent, and change.

If the bishops of the Church of England are being described as ‘weak, woke, weirdos’, then surely the response from anyone who believes in the Gospel is that that is what we should all be boasting in, if we are to model Jesus.

It’s not just about putting Christ back into Christmas; it is about putting Christ back into all of our life.

Christianity is not about tradition or security or making us feel comfortable and reinforcing our current attitudes.

Christianity is first and last and everything else in between about Christ as revealed to us in the Gospels.

And everything in the Gospel is about God’s glory that is shown not through strength, but through weakness; not through exclusivity but through inclusivity; not through continuity but through radical change.

Joseph’s role in the Gospel is underappreciated because he is just one of many men in the Gospel, whereas Mary is one of the few women that play a prominent role.

This is an unfortunate imbalance, and reflects on the cultural traditions of the time that the writers of the new testament were unable to fully break away from, rather than on any eternal principle of how the kingdom of God will be ordered and organised.

If we complain that the church today is straying from traditional ways, then we need to recognise how culturally dependent that tradition is, and how much Jesus was breaking from the traditions of the 1st century when he preached and enacted the Gospel.

Joseph’s role is also underappreciated because he is not an obvious leader, in the same way that the new testament focuses so heavily on certain key apostles and allows the others to fade into the background.

It is again cultural conditioning that we focus on people that we perceive as successful, despite the Gospel making it clear that there is no favouritism in the Kingdom to come.

It is a lesson the modern church often fails to heed, elevating the flashily and outwardly successful over those who offer constant and tireless comfort and ministry, and ignoring that exceptional success is all too often built on shallow, human, foundations, rather than the sure foundation of the Gospel.

It is hard to escape from our cultural conditioning.

Considering Joseph as Jesus’ father sets us thinking about the language we use of God the Father.

For many people this can carry a lot of personal or sociological baggage, as our view of God is conditioned by our experience of family relations or patriarchal models of society, especially negatively.

The problem is that all too often, we are projecting our concept of what a father is onto God, rather than taking the divine model of fatherhood: an all loving, self-effacing, completely sacrificial model of fatherhood, and using that as an expectation that we should aspire our human instances of fatherhood to reach for, even if we can never match.

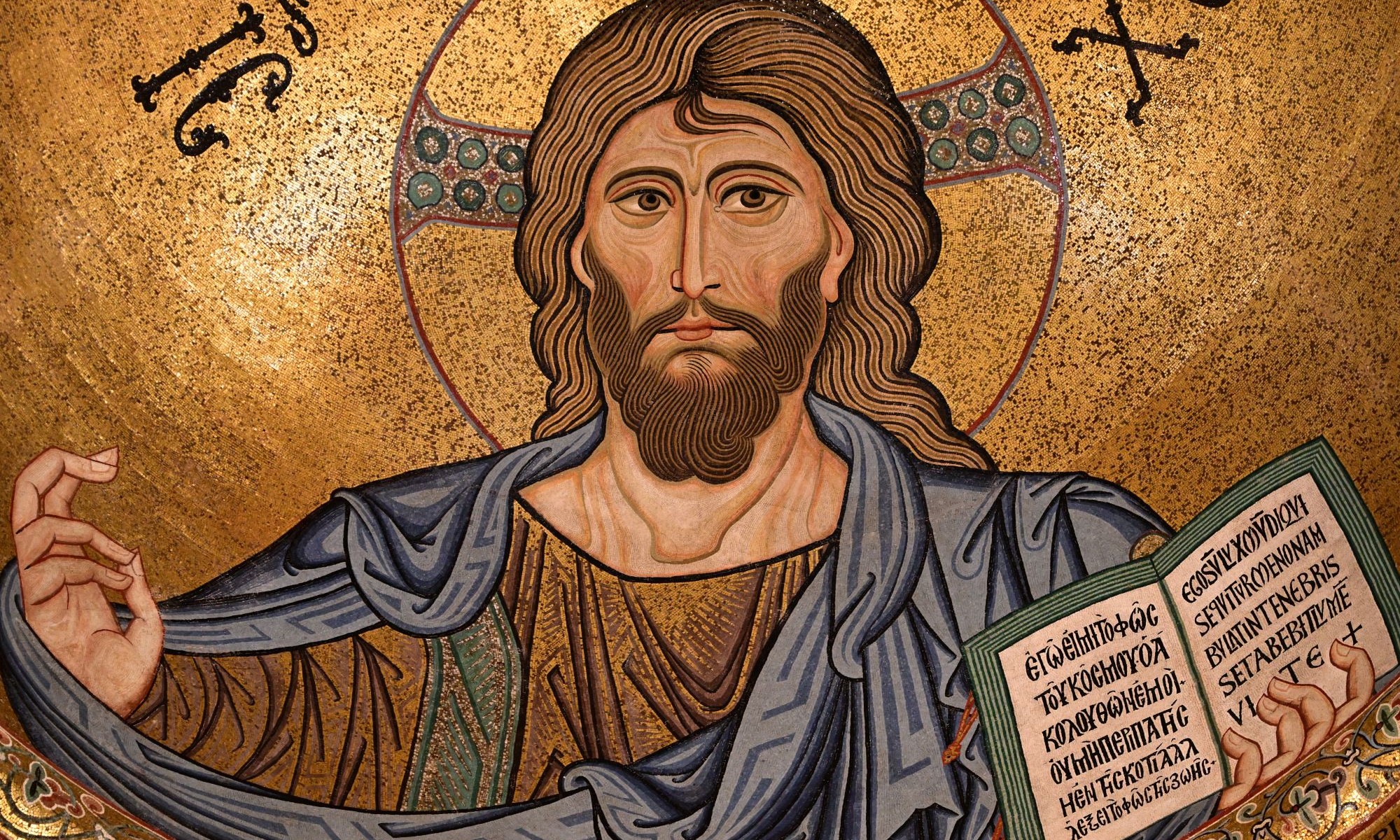

So this Christmas, as we contemplate the holy family, let us think deeply about how we can model the meekness and obedience of Joseph, the courage and righteousness of Mary, and the self-sacrifice of Jesus, divine majesty humbled into mortal human incarnation.

Amen