Second Sunday of Easter 2024. Year B.

Readings: Galatians 4:1-5.

Much of Paul’s literary output seems to be dedicated to trying to sort out his own theological questions, which I suspect is something that links many of us and him, even over the span of two thousand years.

Paul has an outsized influence on early Christianity, probably because of his education and erudition. As he himself tells us, he was taught in the school of Gamaliel, one of the great Pharisee rabbis of the first century. He, like Jesus, is steeped in the scriptures in a way that many of the other leading apostles like Peter, James and John, simple Galilean fishermen were not, at least initially.

This deep scriptural understanding forces Paul to think about the impact that the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus have had on his Jewish history and faith more, or earlier, than we see the other apostles do, although to be fair to them, during Jesus’ life, their expectation is still a traditional Jewish Messianic expectation. They are not forced to re-evaluate this expectation either until after it stops following the script that they had expected.

Paul has a similar, but at the same time completely different change in his understanding. The difference is that we hear less of Paul before his conversion experience.

Paul’s reflection here, in Galatians, regarded as one of his earlier letters, uses some common themes of his, based on the customs of his time. As children, we are not in control of our own actions, but are enslaved by our guardians and trustees. Hopefully not a situation our young people identify too closely with. But then with the coming of Jesus, he doesn’t do the obvious pivot to us becoming adults, possibly because elsewhere he is keen to continue to stress that we are still children and slaves, but to God rather than to the forces of the world. Instead, he introduces one of his other great ideas – that of inheritance by adoption, to explain how the covenant that the scriptures had made clear was for Abraham and his descendants could become available to everyone.

Adoption was a big thing in the Roman world – for noble houses where lineage was everything, adoption of a relative, or even a trusted ex-slave on occasions, was the best way to ensure that the noble line continued without interruption. So the language of adoption for Paul may carry very different overtones to what adoption might mean for us today.

What is consistent in Paul’s writings is an overtone of dispensationalism – the idea that God’s revelation had been progressive throughout history. First to the Jews in the covenant with Abraham and then with the law of Moses; then later in a completely new covenant based on Christ and the cross. This finds its most explicit expression in Paul’s letter to the Romans, with its contrast of Jews living under the law and Christians redeemed through grace.

This, along with other of Paul’s writings, have, unfortunately, throughout history led to a degree of justification for anti-semitism, and a characterisation of Judaism as being narrowly legalistic, which ignores the breadth of belief in second temple Judaism, and the emphasis on divine grace that is evident in extant writings of the Pharisees and Essenes.

What Paul is trying instead to do, rather than castigating his own race, is to find the fulfilment of God’s promises – not just those to Abraham and Moses, but also the earlier ones to patriarchs such as Noah – find the fulfilment of these covenants, not just in Israel, but in the whole world, including Israel as God’s faithful servants, culminating in Jesus himself.

In doing this, and in trying to work through this thoughts on this, he introduces a whole new idea, one that fell on more fertile ground in the eastern church than in the western church.

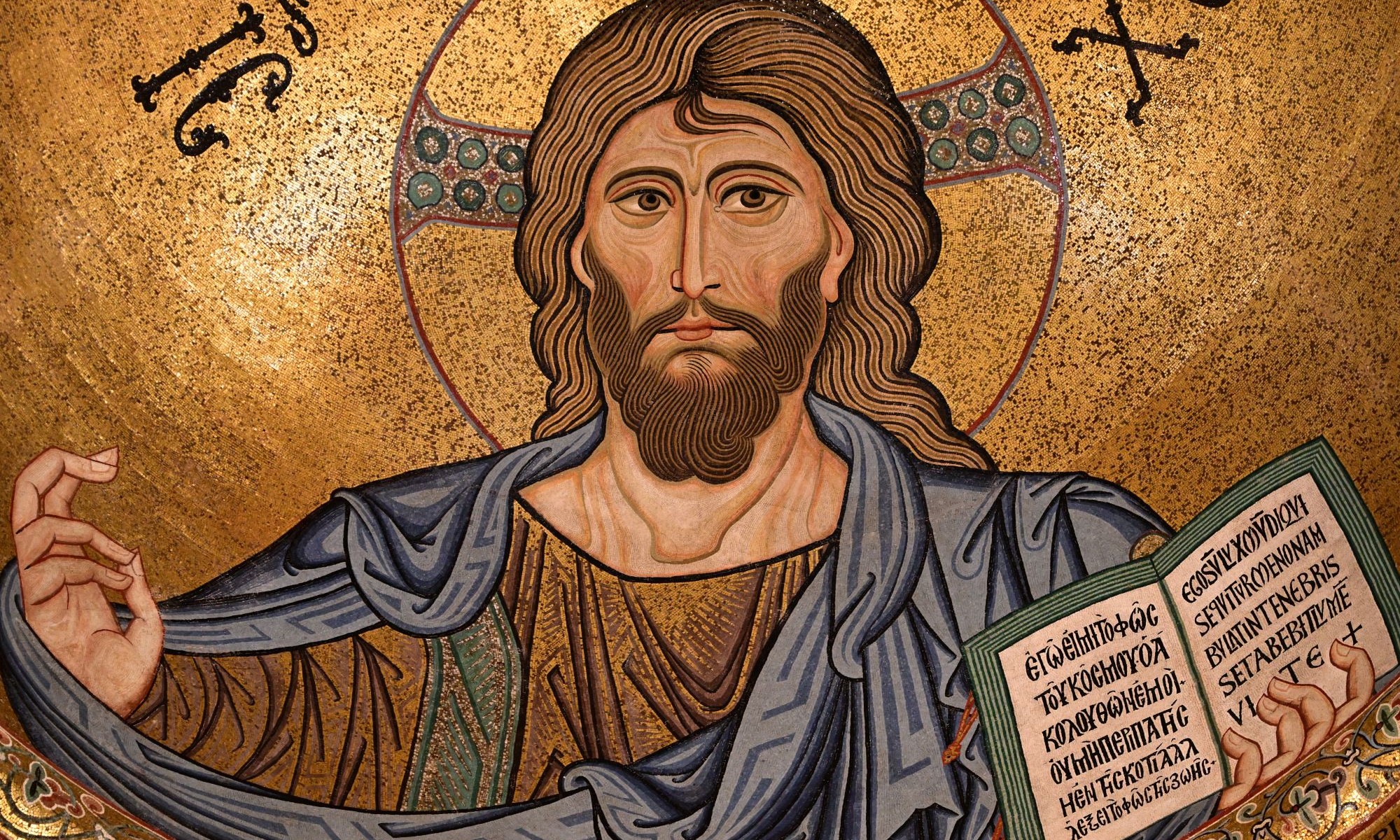

This is the idea of deification – that Christ became human so that in some way, through his incarnation and scrifice, we might become more divine.

Here it finds one of its earliest vocalisations, the idea that we, as adopted children, can share in God’s own divine nature, through the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, who in living and dying as one of us, brings us closer to being one with God.