Evensong, 2nd Sunday of Lent, 2023. Year A.

Readings: Numbers 21.4-9 & Luke 14:27-33.

Sometimes when writing a sermon you get two readings that relate to each other in a very obvious way, either through the intention of the lectionary compiler, or because they also interact with the events of the day in a particular way. This evening didn’t feel like one of those evenings.

The first reading we heard was from Numbers, and is one of those strange passages in the Pentateuch that really make you wonder if they have crept in by mistake, a bit like the one in Exodus where God attacks Moses in the night just after having given him his mission to go to Pharoah.

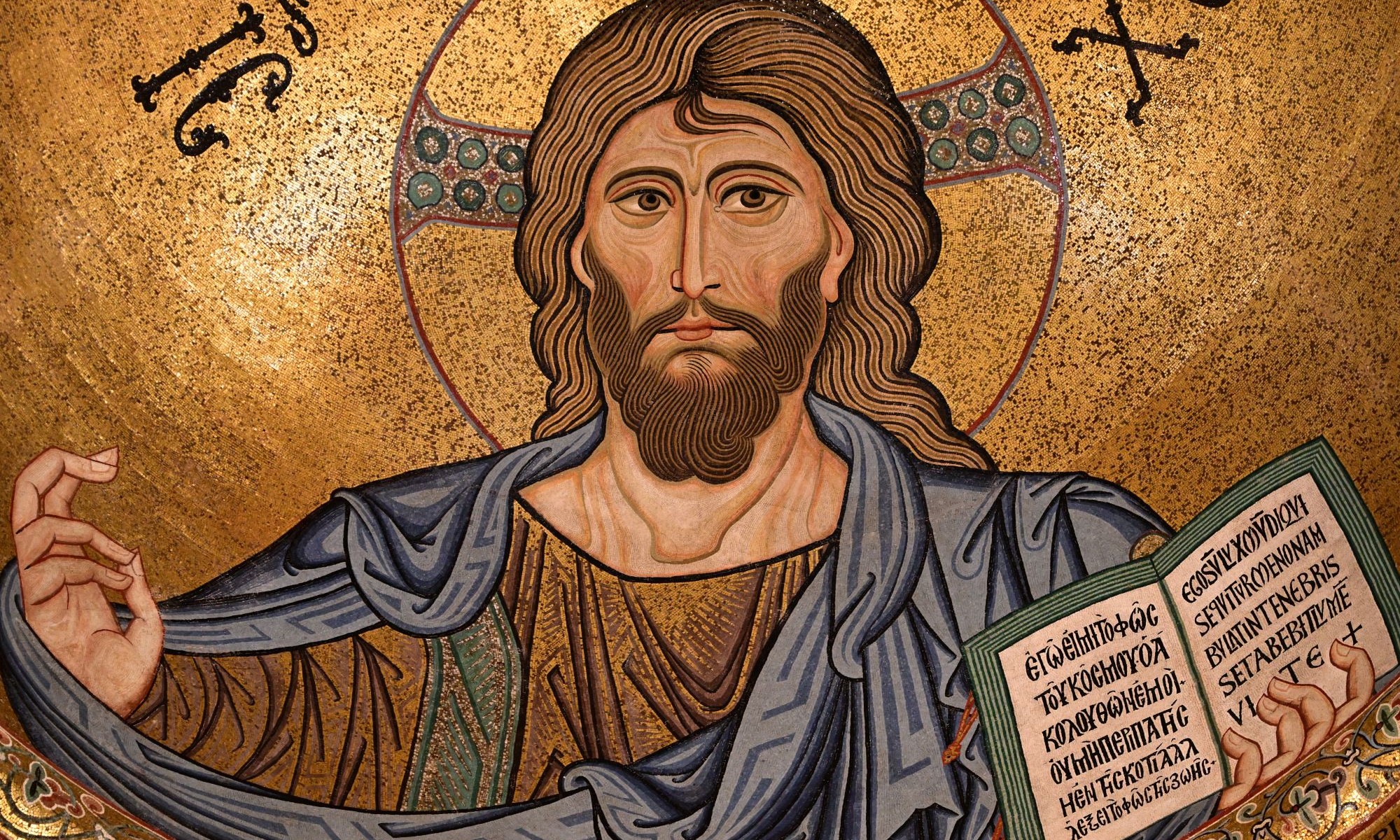

The Israelites, detouring through the wilderness, complain once again about the conditions. God gets angry and sends poisonous (or maybe fiery) serpents to bite them. The Israelites repent and ask Moses to intercede – he does, and so God tells him to make a bronze serpent on a pole, and everyone who sees the bronze serpent doesn’t die when a snake bites them.

Why doesn’t God just stop sending the snakes?

This is the bronze serpent, by the way, that King Hezekiah destroys in 2 Kings 18 verse 4, because the people are worshipping it with incense, and treating it as an idol.

And maybe this is a clue to how we should be treating this passage. Like much of the Bible, we shouldn’t be looking at this as literally true in a historical sense.

If we do so, we just devalue the truth that is in the Bible.

Instead, this is a mythological passage.

In Jerusalem there was a bronze serpent on a pole that people said was originally made by Moses. This story is a myth explaining why the temple had a bronze serpent on a pole that was made by Moses, despite it being somewhat inconsistent with later religious practice.

Does this mean that the Bible is not telling the truth?

No, it doesn’t. Because in this case the Bible isn’t about literal historical truth. In this case, the truth the Bible is telling us is about the relationship that Israel saw itself having with God through the ages. The ways in which they understood providence – how blessings and curses came from their behaviour. This is a true account of their relationship with God.

To us now, it makes for tales of a God who can seem vindictive and un-loving, and also wildly inconsistent, if we have a more classical view of God as unchanging and benevolent. But the Old Testament experience of God was different, and this was a different people in a different place and culture that it is hard for us to really understand.

Christianity has a scandal of particularity – Jesus was incarnate in a particular place, Judea, at a particular time, the first century AD. We can see this in our Gospel reading. The examples that Jesus gives are just examples that his audience of the day would have understood. They are probably not personal experiences – few of his audience would have built a tower, or decided to wage war on another king, but they are comprehensible, and the weightiness of them helps to emphasise the weightiness of the decision that Jesus is asking his audience to make. We should not be analysing these examples in detail – he is not giving project management advice to anyone considering an extension – but focusing our attention on the first and last verses of the passage, and the verses we haven’t heard that immediately bracket it – his demand that we cannot follow him unless we hate our families and indeed life itself, and his exhortation about the value of salt.

Jesus here is speaking in prophetic mode – in broad brush strokes, with exaggerated metaphors to emphasise the importance of what he is saying. Again, this is not to be read literally. If it were, the ranks of true Christians would be reduced to a mere handful of friars and monastics, for who else amongst us have given up all of our possessions?

When the Church of England licences or ordains, one of the declarations states that the duty of the church is to proclaim the faith, revealed in the Holy Scriptures, afresh in each new generation. Scripture reveals faith – it is not faith itself. And that faith must be proclaimed afresh in each new generation. Because of the particularity of Jesus’ incarnation, we cannot look to his literal words as a guide for all the ages, because he spoke in a manner which would enable his audience of the time to understand. Jesus was eternal, but his audience we of that time.

We are not that audience, and we deny two thousands years of the outworking of God in the Holy Spirit if we demand that we should still be that audience, and should still understand God in the same way that they did. Jesus says that we must carry the cross and follow him to be his disciple. He does not say we must follow the law to be his disciple. He does not say that we must quote scripture to be his disciple. He points us to the cross instead, the non-verbal symbol of his divine willingness to suffer and serve us, in order to reveal God’s unending love for all of his creation.

In the shadow of that cross, we are called to proclaim the faith afresh, and the source of that faith is the true word of God, not scripture which reveals the word of God; but the true word of God, the logos, the Son that died for us, and was raised on the third day.

Amen.