17th Sunday after Trinity, 2023. Year B.

Readings: James 3:13—4:3, 7-8a & Mark 9:30-37.

The epistle of James is not one of the better known of the books of the New Testament. This is unfortunate because James is a key figure of the early church, and his letter provides a unique view on early Christian theology.

One of the possible reasons why James is so ignored, especially in protestant circles, is because it can easily be seen as contradicting Pauline theology, and proposing a doctrine of works which the early protestants associated with the excesses and abuses of the Roman Catholic church of their times, rather than a doctrine of salvation by faith alone, that Luther and the other protestant founders found in Paul’s letter to the Romans.

This is a somewhat simplistic reading of both epistles though, and also very rooted in the context in which Luther found himself. If we look back to the original context of the epistles, I think we can recognise that Romans is far from the academic theological treatise that it is sometimes claimed to be.

Instead it is, like all of Paul’s epistles, written at a particular time, to a particular church and for a particular reason. In the case of Romans, it is the only letter written to a church that Paul did not found, and therefore lacks some of the more personal and pastoral content that his other letters contain.

This is not a church that Paul has particular influence over, or that he is admonishing or teaching. Instead, this is a long established and influential church of its own, being present in the capital of the Roman empire, but one which we now think probably had deep divisions, following Claudius’ expulsion of the Jews from Rome. It is likely that many gentile Christians remained in Rome, and when the Jews returned after the death of Claudius, there may have been rivalry between the two groups on who was going to lead the Roman church.

Certainly it was a church with a strong Jewish character, which is why Paul is so keen to stress his Jewish credentials in the letter, and also why he spends so long in justifying why and how gentile Christians can be included as those justified in the eyes of God.

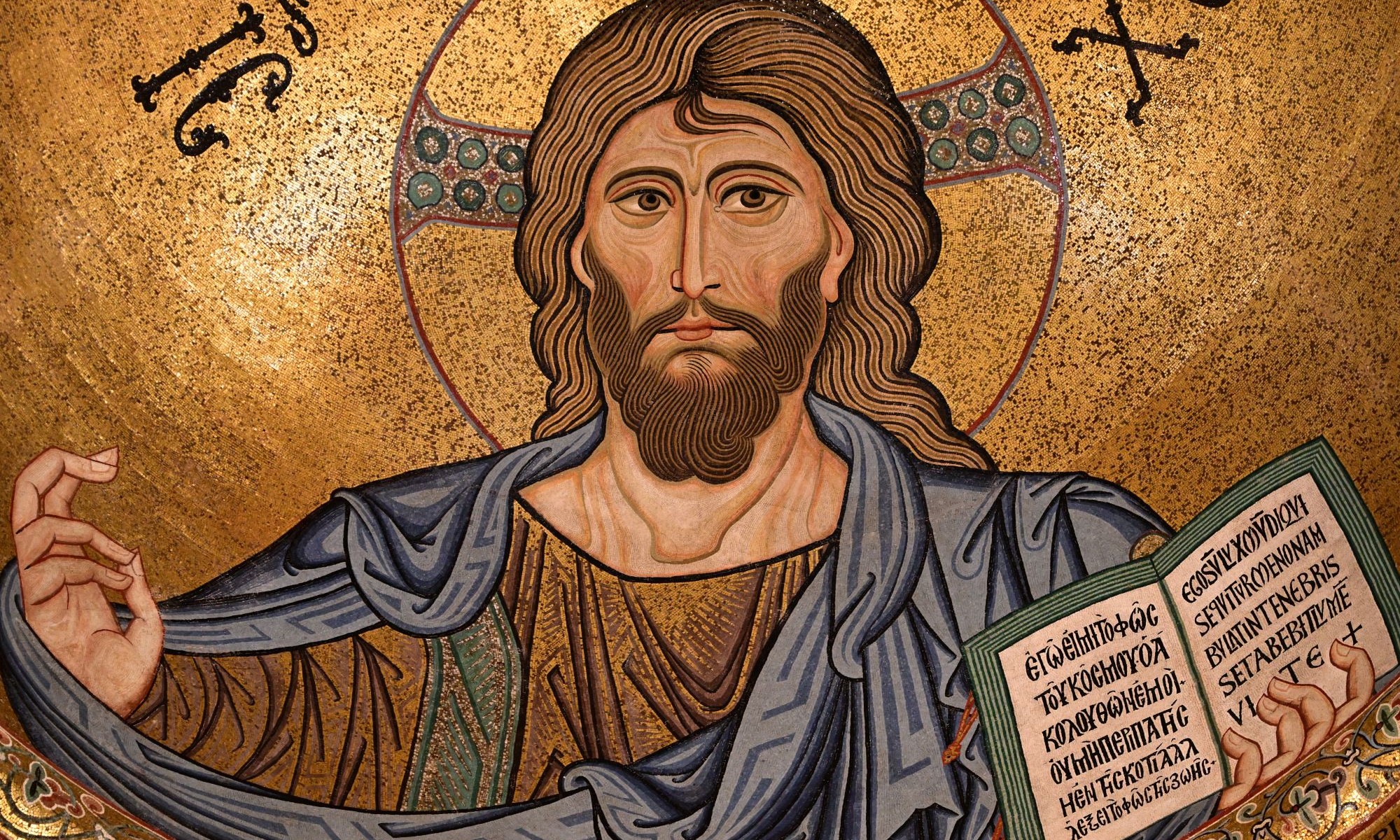

Faith is key to this, not just the faith or faithfulness of those gentiles, but also the faithfulness of Christ to both the ancient covenants and to the wishes or will of God. This faithfulness of Christ, the Jewish messiah, is the key bridge that allows him to justify both Jews and gentiles, and Romans is a long and carefully reasoned letter to persuade the Jewish Christians of this.

This Jewish Christian faction or party is one that Paul has locked horns with many times, and its leader was James, who wrote our epistle. James, also called the Just and the brother of Jesus, was the leader of the Jerusalem church up until his martyrdom at the instigation of the high priest some time in the sixties AD. He is the James who presides at the council of Jerusalem and proposes the compromise that allows Gentile Christians to avoid having to follow the whole of the Mosaic law. He was widely regarded by all the Jews as a pious and devout man, which may have been why it took so long for the authorities to move against him.

We think that the church in Rome was probably started by Jewish Christians from Jerusalem who followed many of James’ teachings, which is why Paul needs to go to such pains to assure them of his Jewish Christian roots, given what seems to have been a history of antipathy between him and James.

James, from his letter, has a theology that seems more rooted in the gospel teachings of Jesus about living a righteous and just life, rather than some of the more spiritual theology of Paul’s epistles.

This seems entirely appropriate for someone who was one of Jesus’ disciples as well as his brother, and whose congregation was mainly Jewish, and therefore inhabited the same culture as Jesus was preaching to.

James therefore is almost certainly one of the disciples that we hear about in our Gospel reading today, arguing over who amongst them was the greatest. It is possible indeed that James would have been establishing a case for himself, given his relationship with Jesus. We never find out unfortunately what other criteria are being advanced? Length of acquaintance? Miracles worked? Lepers healed? Closeness of friendship?

What we do know is that Jesus uses this to teach them something of the nature of Christian leadership and behaviour. Christian leadership is about service, to each other and to the world.

The disciples have faith in Jesus – they have given up their families, the livelihoods and their homes to follow him as teacher, prophet and messiah. But that faith in him is not yet translating itself into the behaviour that Jesus expects of them, and Jesus is always very clear that words without action are not sufficient. The repentance that he is calling all people to is a physical repentance, a turning round of their lives.

He is also clear that it is not about putting ourselves first. A superficial reading of some of Paul’s writings can make us think that our personal salvation through faith is important, but I think Jesus is making it clear that we are to put others before ourselves. Our role as Christians, as leaders, as lights to the world, is to put the needs of the world first, and ourselves last.

Mission, literally going out, is what being a Christian is all about. God doesn’t help us by waiting for us to come to him. Instead he sends his son to become one of us, live amongst us, become human, while still at the same time remaining God. In the same way, we are called to go out into the world, meet people where they are, live amongst them, while still at the same time remaining distinctly Christian.

James is the first to admit that this is difficult. We are still profoundly human, and therefore we carry all the troubles and weaknesses of being human with us. We should rise above them through the grace of Christ, but all too often we fail. We should and would like to be recognised as Christian by our actions, and bear witness to the gospel in all that we do, but unfortunately we have in the past and continue to fall short.

Our response to this though should not be to withdraw from the world, or hide ourselves from it, but to redouble our efforts, admit our shortcomings, ask for forgiveness. Whatever the world asks of us, we should do twice as much for the joy of life in Christ.

As an example, given our gospel reading, when we seek to welcome children amongst us, we would like to be trusted as Christians that we would only every thing to treat them as Jesus commands us in the gospels, as our neighbours and fellow citizens of the kingdom, but historically all to often we have failed in this, and abused positions of power and privilege. The response to this is not denial and secrecy, but should be to embrace safeguarding not as a chore, or a secular imposition, but instead an expression of our common failings and repentance, and of our determination to live a gospel-inspired and Christ-like life in the future. We should rejoice in the opportunity to demonstrate to the world what the kingdom will look like, where all are valued and respected equally.

What then is our mission as a Christian community? What are our values, and how will we live out these values, not here in this building on a Sunday morning for an hour, but for the other one hundred and sixty seven hours of the week in the world that we have been sent into, to be a light to?

Next weekend we have a chance to think, debate, meditate and pray on what our mission is, not just individually, but as a community. How are we going to be that city on a hill, the light on the lampstand?

It is easy to be overwhelmed when we think about Christian mission. The world is a big and broken place, and we seem few and poor in comparison. We are not called upon to do this alone though. There are I think two considerations that we need to remember as we prepare for next weekend.

First we are called to do this as a community by God, and God will always be there to help and support us. Nothing that we do will bear fruit without God, although God will work through us, as he worked through his Son.

Secondly we are in the context that we are in, alongside many other churches in contexts both similar and very different. We have the gifts and skills we have in the place we are, and we should be seeking not to emulate others but to serve God in the way best suited to us.

We are blessed with many gifts amongst us, gifts of money, time and skills. Empathy, love and understanding, Talking, listening and doing. We are called upon to grow the kingdom of God, let us do so with a vision that is bold and clear and Christlike.

Amen.