Thirteenth Sunday of Trinity, 2018. Year B.

Reading: John 6:51-58

The Bible talks about bread a lot. It’s a very potent image. In those times bread was truly the staple of life.

For most people it was probably three-quarters of their diet, supplemented by seasonal vegetables or pulses, and enlivened by the odd bit of fish or, on festive occasions, some meat.

So when Jesus talks about bread, he is using a metaphor that they can completely relate to. For them, far more than for us, bread is life.

For me, bread is a comfort food – stable, traditional. I’m just old enough that it raises the image of a delivery boy struggling up a cobbled hill to the sound of Dvorak’s New World Symphony.

For his audience, Jesus reminds them of the key event in their history – the exodus from Egypt. When they were wandering in the wilderness, God gave them manna to eat – bread from heaven.

Manna is what God gave them in the wilderness, before they came to the promised land, during the forty years that they spent purifying themselves and becoming worthy to cross the River Jordan.

Just as their forefathers were given bread by God in the wilderness before they reached the promised land, now, again He is giving them bread from heaven in the person of Jesus, because once again they are in the wilderness searching for the promised land, as are we.

We too are still in the wilderness, still on our way to the promised land, being purified before we can enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

In one respect, we have crossed the river Jordan, at our baptism, and we are part of the Kingdom, but the Kingdom as Jesus described it is still yet to come.

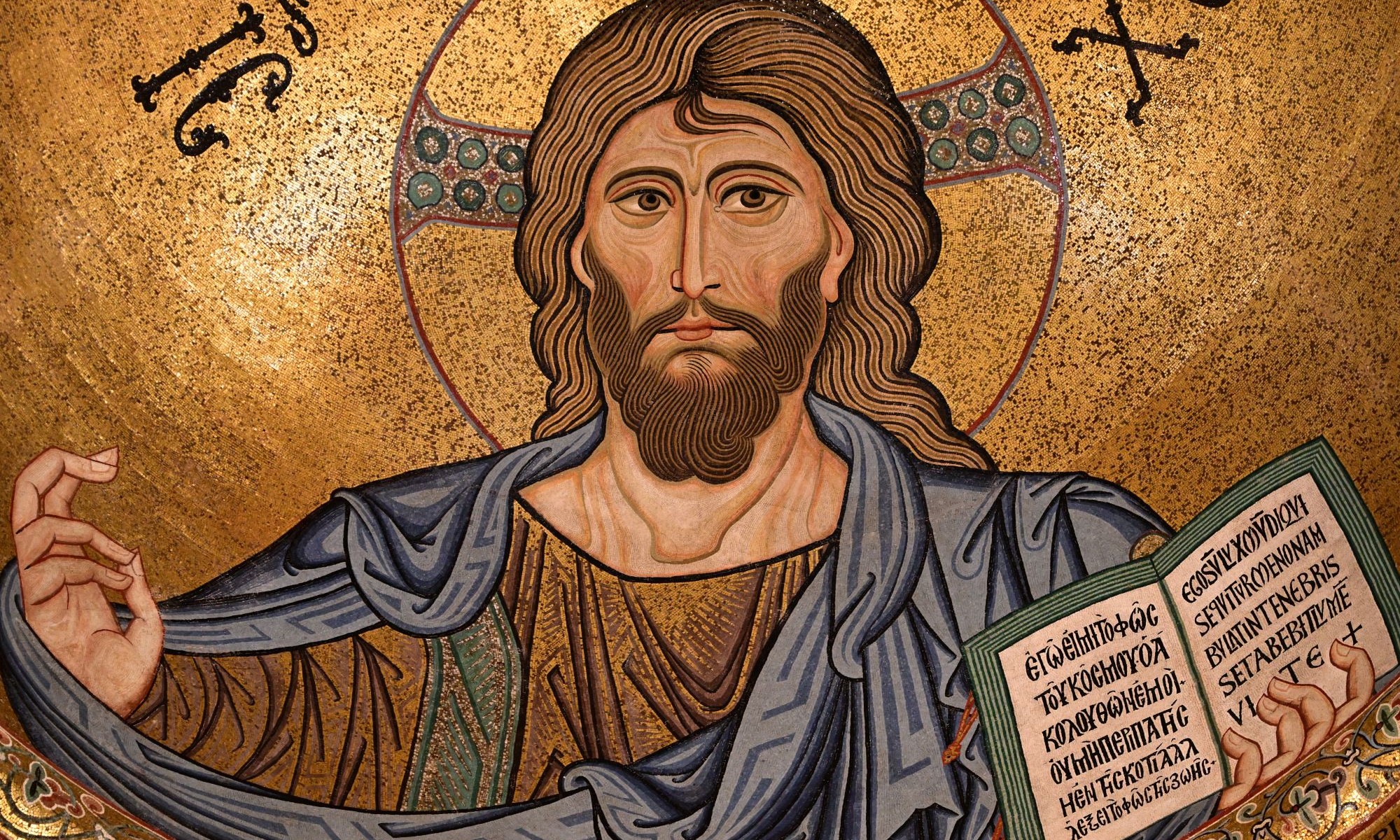

In the Gospels we get a glimpse of that Kingdom in the person of Jesus.

Wherever he goes, the Kingdom surrounds him. Wherever he is, the sick are healed, the marginalised are included, the unworthy are made worthy, and the dead come back to life.

We are given a glimpse of that kingdom in the Gospels, but rather than embracing it, we turn against it.

Jesus dies on the cross, and it seems like the kingdom is no more.

We are still in the wilderness, searching for the promised land.

But our prayers are answered. Jesus rises from the tomb, and the glimpse of the kingdom is restored.

It surrounds the disciples too now, and it becomes the role of the church, and all of us, to be that glimpse of the kingdom.

We are still in the wilderness, but we have the bread from Heaven, Jesus, that enables us to survive through the wilderness to reach the promised land.

So we gather here, week after week, as the Church, to partake of that bread from Heaven, in word and sacrament. This week, especially, serves to remind us what an incredible gift the eucharist is. Sometimes you have to lose something to truly value it.

John is notably different in his account of Jesus from the other three Gospels in many ways, and especially in his description of the Last Supper.

John places Jesus’ command to eat and drink his flesh and blood to this passage, and gives it a different, yet complimentary, theological spin.

In the synoptic accounts of the Last Supper, Jesus tells them ‘do this in remembrance of me’.

The eucharist is there to remind us of Christ’s sacrifice for us upon the cross.

John moves the description of the eucharist from the closed, personal space of Jesus with his trusted disciples to here, in front of a great and querulous crowd.

And John emphasises Jesus describing this as the route to eternal life.

Here, the bread that God gave them in the wilderness is a metaphor for the Law, given to them by God at Mount Sinai.

But Jesus is saying that the Law will not save them. They can only be saved and given eternal life by Jesus, the true bread from Heaven.

And when Jesus tells them this, he is challenging them both directly and indirectly.

It might have taken his listeners a while to work out that when he talks about the bread they were given in the wilderness, he is also talking about the Law, but the language he uses is directly challenging them.

In Jewish dietary law, blood is strictly forbidden. Asking people to drink blood is offending their deepest taboos. Not for them black pudding and rare steak. In Leviticus God makes it quite clear that blood is life, and that all life belongs to God.

Even if they take his words metaphorically, the idea of eating your God’s flesh and drinking his blood would have been redolent to them of the idolatrous Greek and Egyptian mystery cults that were so popular at the time.

This is not Jesus asking them to accept him as part of the evolution of Jewish history and religious experience.

This is Jesus asking them to make a radical break with their past and think anew on what living the way that God wants really means.

Even his disciples find it hard to understand and accept what he is saying here.

Oftentimes Jesus will answer a question with another question, getting the questioner to thing themselves about what God is asking of them, rather than just feeding them a stock answer.

Here he gives an answer, but even that just creates more questions, because the answer isn’t what they are expecting.

It is notable that Jesus very rarely lays down general laws.

When confronted with situations where a moral or ethical judgement is called for, Jesus does exactly that; he judges.

He weighs up the situation in the light of the people and events involved, and then applies the justice and love of God to decide what resolution is best for the people involved.

Not necessarily what is best for them in the short term, or individually, but what is best for everyone in the long term, so that they can all live the sort of lives that God wants them to lead.

The Law is made for man, not man for the Law. God gave them the Law in the desert as a staff to help them, not a chain to bind them.

They are coming out of generations of slavery in Egypt, where their decisions were all made for them. At the bottom of society, they would have seen rules as a way for the powerful to abuse and exploit the weak.

The response to this is not anarchy though, and, the Law is given to them by a loving God as a guidance, to help them rediscover their freedom in a responsible manner.

It is not perfect, because they are not perfect – it is tailored for them and their needs.

Where they have then gone wrong is to idolise the Law, to raise it up on a pedestal and make it their sole guidance.

God tries to help them see the error of their ways – he sends prophets to show them that God is not about rules and checkboxes, but is instead about love and justice.

And finally he sends his Son, Jesus, the living law, the bread from Heaven that will bring eternal life.

And Jesus tells us that the Law cannot be something external to us – a set of rules written down in a book somewhere that we mark ourselves against day by day.

The true Law, the Living Law that gives us eternal life, needs to be internal to us.

We understand this law by consuming the Logos, the Word of God made flesh, by taking that Word and bringing it into ourselves.

When we bring it into ourselves, we need to look at every decision we make, every action we take, and ask ourselves whether we are following the Law, the Living Law, not just a bunch of rules.

If we do this thing, are we fulfilling God’s purpose in the world when we do it?

Are we expressing God’s love for all the world?

Are we loving our neighbour as ourselves?

Keeping to a set of rules is easy, because the rules are all written down, and hard, because there are so many of them, and they often fly in the face of our sense of natural justice.

Keeping to the Living Law is hard, because we have to think for ourselves, be constantly be thinking deeply about how we act and the impact it has on ourselves, on others and on God, but also easy, because deep down, we know that following the Living Law is our true desire, and our true wish, because ultimately it will bring us closer to God.

This then is the bread from Heaven that Jesus offers us when we let him into us.

Amen