Eighth Sunday after Trinity, 2020. Year A.

Readings: Matthew 14:13-21

The feeding of the five thousand feels like quite a simple story. It’s one of the first bible stories that we learn about as children if we are learning about stories of Jesus.

And there is a reason for this.

It’s a pretty easy story to understand. A lot of people come to listen to Jesus, and most of them forget to bring a packed lunch. He talks to them, and heals people and then, when it is getting late, he miraculously feeds them. Although of course, he has been doing miracles all day, healing them, as well.

Communal eating has always been a key part of our social lives as humans. We eat together to reinforce our sense of community, of being together. As families, as groups of friends, and as church.

But what Jesus is doing here is more than just bringing all these people together.

He is showing, in action, what being the Messiah is all about.

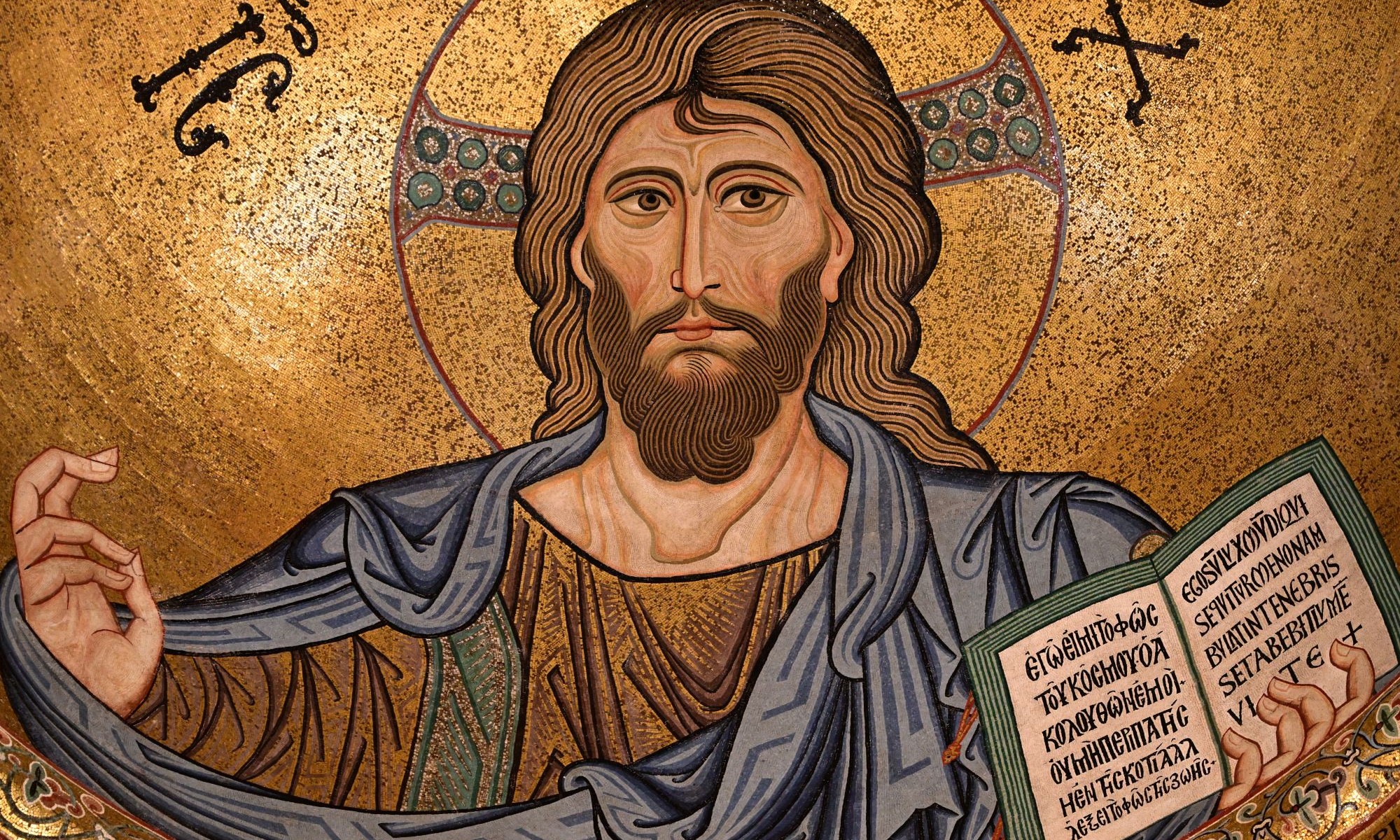

And he is showing us that in him, all of time is gathered. He is the centre-point of history. In his now, is all of the past, and from it, all the future flows. All in the simple action of feeding 5000 people, with just 5 loaves and 2 fishes.

In the present moment, he is showing us what the good news is.

He has spent the day healing the sick, now he feeds the hungry. He is showing these people, and us, what the Kingdom of God that he preaches about is really like. The sick are healed. The hungry are fed.

He is also showing them what it is not.

It is notable that this miracles occurs in the wilderness, where Jesus has retired following the news of the death of John the Baptist. That death would have been big news at the time, because John the Baptist was big news at the time. Maybe many of these people were following Jesus into the wilderness because they thought he would now take on the mantle of John the Baptist, and become a voice, crying in the wilderness? Maybe they thought that his death might provoke Jesus to raise the standard of rebellion in the wilderness, like the Maccabees had two centuries earlier, overthrowing the hated Seleucids.

Jesus is coming into the wilderness to prophesy about the Kingdom of God, and he is declaring himself the Messiah, but not in an expected way. He is forgiving sins and healing people, which until now has only been permitted through the sacrifice system in the Temple.

He is feeding thousands of people with bread, which is what Caesar did in Rome to demonstrate his power and majesty. In its own, non-aggressive way, feeding the five thousand is just as much of a thread to the rulers of the world as raising any standard of rebellion. Jesus is showing that anything Caesar can do, he can do as well, but he doesn’t need to ship his bread from Egypt. His bread comes from heaven.

And this is where he ties himself back into the past; the history of Israel. Like this crowd, the Isrealites who left Egypt with Moses found themselves in the wilderness with nothing to eat. And for them God provided manna from heaven, for 40 years. Even down to Jesus’s day, a jar of manna was kept in the inner sanctum of the temple, to remind Israel of the time when their entire survival has been completely dependent on God’s gifts.

So by feeding the five thousand (and later the four thousand, so we must assume this wasn’t a one-off; this probably happened several times); by feeding them, Jesus is showing them that he is the Messiah; that he can fulfil the role that God has filled in the past for Israel. In him, all the history of Israel comes to its triumphant conclusion.

And at the same time this is a feast. He is not just feeding them with bread, but with fish as well. In Greek and Hellenistic culture, food was generally divided into two types. There was the bulk food – the stuff you ate to survive, like bread and beans, and pulses and even meat. You normally only ate meat because it had been sacrificed in a temple, and then the priests tended to take the best bits, so you were left with the less appetising cuts. The other sort of food was the appetisers – the bits you ate to make the meal exciting. For the Greeks (and probably for other biblical period peoples, fish was really important – fish were never used as sacrifices, so you go do what you wanted with them; and they had a lot of flavour. So in serving both bread and fishes to the crowd, Jesus isn’t just filling them up so that they can survive. He is giving them a proper feast.

Feasts play a big part in the Gospels. Jesus was obviously fond of socialising and meeting people, especially over meals. And he often uses parables about feasts to describe the Kingdom of God. It will be like a great feast to which all will be invited. Feasts in Roman times, like formal banquets now, were opportunities to display the social pecking order. Those of high status got to recline nearest the host. Those of lower status would stand or sit further away and only get what the top table didn’t finish. But Jesus always makes it clear that his Kingdom will be a feast where everyone is welcome and treated equally. This is one of the reasons that Paul gets so irked by the Corinthians in his first epistle – they are not sharing properly between rich and poor at their weekly eucharistic meal, but the eucharistic supper is not just a communal meal following the normal social rules of the time – it is a model of the world to come.

So in giving this feast to all these people, Jesus is showing them his vision of what the future will one day be. This is a little bit of the kingdom to come, in the kingdom of the present. We live in this time as well – the time when the kingdom is here, and is also yet to come. It is hard to be in this ‘not quite’ state, but fortunately Jesus has left us with these models of how we can enact the kingdom that will one day come.

It has been harder still in these times of lockdown, where even the symbol of a meal eaten with friends and relatives and neighbours has been taken from us. For some of us there is a relaxation, an ability to gather once again; for others there is still the need to shield and protect themselves. And yet we have come through this period in fellowship and caring for one another. It was a mark of the early Christians, noted by pagan writers, that during the cycle of plague outbreaks in the 3rd century, when others would flee the victims of plague, Christians would continue to care for them, at personal risk. It was such counter-intuitive behaviour, it left a great impression. We, fortunately, have not been confronted with something as terrible as plague, but the way we have cared for each other is, for our generation, an enactment of the kingdom to come.

And yet we are faced by this pandemic with challenges that are new to our generation. We are able to meet, not sitting on the ground in the wilderness, but in this church building, sanctified by generations of worship from this community.

We are now part of the establishment, rather than being rebels and outsiders, even if we are still called to be a challenge to the world.

It can be easy to fall into a comfortable familiarity, even to see the church as more of a social club than God’s people on earth.

The pandemic has put strain on people, on communities, on finances and on priorities. It calls us to evaluate what is central to God’s mission with which we are entrusted.

Things that we have taken for granted, we can no longer take for granted; and that should be a good and fruitful thing, if we approach it rightly, and prayerfully.

So let us use this opportunity that we are given to reflect on our faith, our mission and our church. Let us evaluate what is the bread from heaven, and what is the earthly bread; what is the basic stuff of life, and what is the appetizer that God has given to us on top of that.

Amen.