Christmas Day, 2025. BCP Communion.

Happy Christmas everyone.

You may not have noticed it in the hurley burly of all the other news that has been happening recently, but this year was the seventeen hundredth anniversary of the council of Nicea.

This was the first great council of the church, and gave us the first draft of the Nicene creed, which was devised to try and bring some sort of unity back to a divided and fractured church – plus ca change…

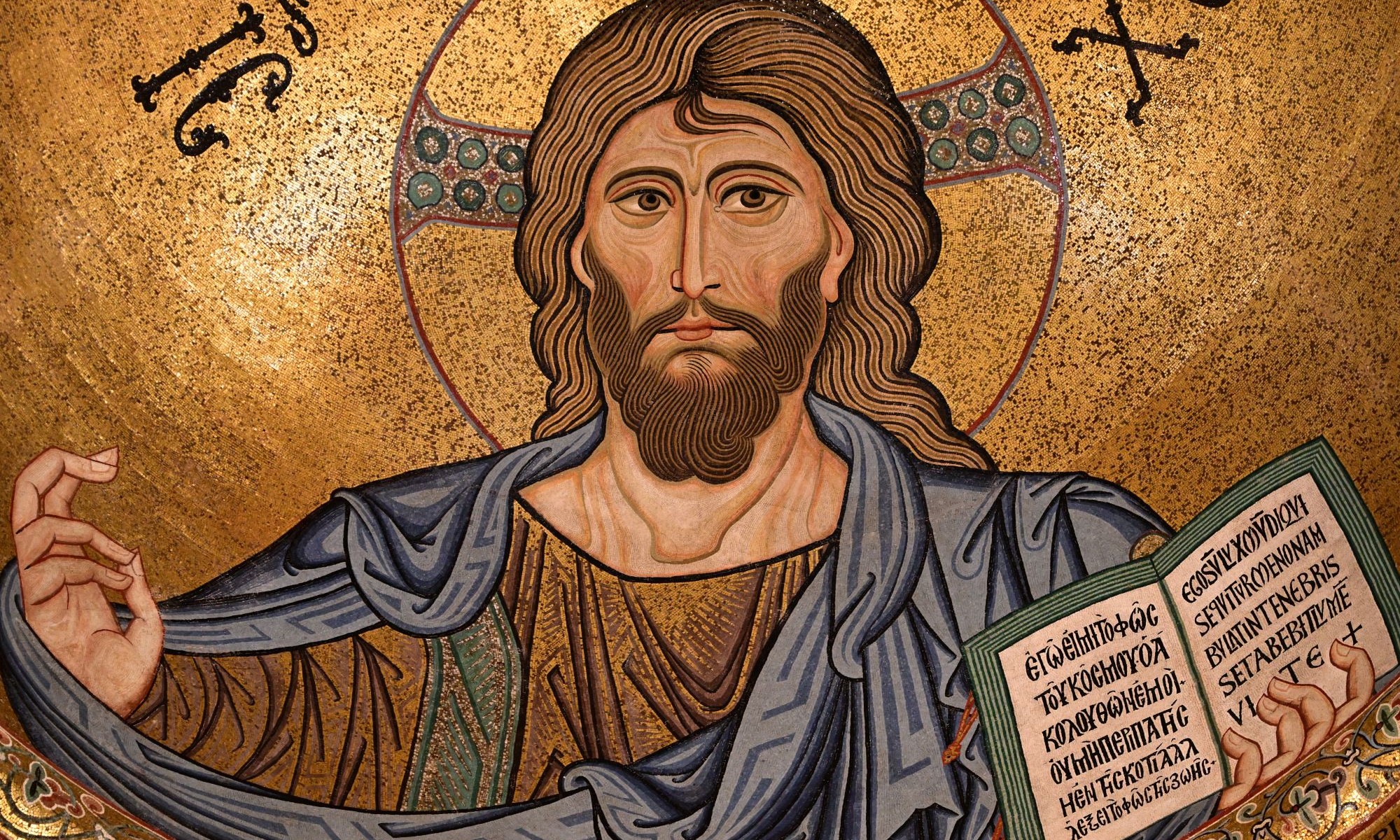

And the question that was most vexing the church in 325AD is the question that is first posed on Christmas Day, and to which John, Matthew and Luke all dear witness to in different ways. Mark, of course, just completely dodges the issue. The question of course is who is Jesus?

Everyone could agree, like Peter, that he was the Christ, the Messiah, the anointed one of God. Both Luke and Matthew make it clear that he was more than just human; conceived by the Holy Spirit of the Virgin Mary.

But only John explicitly claims that ‘the Word was God’. That this person of Jesus, seemingly fully human, was in actuality fully divine.

For several centuries much ink, and sometimes blood was spilt over this claim that Jesus was truly God.

And after the Council of Nicea, even more would be spilt over the question of whether he was also truly human as well, and if so, how his human and divine natures were reconciled in one person. It needed the Council of Chalcedon to sort that one out.

Does any of this matter to us today?

It is very easy to just take for granted that Jesus was truly God, and that he was also completely human at the same time.

We are so used to affirming it that for much of the time, our minds don’t rebel against this in the same way that the theologians of the early church did, for very sensible reasons. They sought to protect Christianity from pagan polytheism. They didn’t want to water down the otherness of God and distinction between creator and created.

They wanted to maintain the neat categories of their philosophical constructs.

God becoming man doesn’t make any sense…

But Jesus doesn’t fit into neat categories.

He doesn’t come to confirm the status quo.

He is not here to make us feel good about ourselves, but instead to make us feel bad about ourselves, so that we can start to feel better about ourselves.

This is the violence that Jesus promises that he brings in the Gospels.

Not violence of the world; the physical violence of war and oppression – we can do that quite well by ourselves.

Rather violence of thought and spirit. Violence that breaks our complacency, our willingness to go with the flow, to not make waves, to not stand up for righteousness and justice for all.

Violence that starts with his very existence. God from God. Word made Flesh.

A God who so loves all of His creation that he partakes fully of himself in every aspect of that creation. From destitute birth to violent death. Not just a cute baby in an idyllic pastoral scene, but rather a total reordering of creation as God’s infinite love breaks in.

After Christmas, nothing is ever the same again…

Amen.