Ascension Sunday, 2022. Year C.

Readings: Acts 16:16-34 & John 17.20-26.

May the words of my mouth and the meditations of all our hearts be acceptable in your sight, O Lord, our refuge and our redeemer.

Ascension Sunday is one of the two liminal points in the church calendar, the other being Holy Saturday. Like Holy Saturday we are caught between despair and joy. I don’t know if the despair felt less for the disciples on Ascension day than it had done on Good Friday – obviously witnessing Jesus coming in glory to the father must have been a much more uplifting experience than seeing him flogged, tortured and nailed to a cross. But at the same time, the sense of loss must still have been extreme. The kingdom had come with Jesus, and then been snatched away from them on Good Friday, only to return triumphant on Easter Sunday. Now, a mere forty days later, Jesus was leaving them again. They would be excused for being overwhelmed by the speed at which events were taking place, and confused as to how all this fitted in with the prophecies that they had been brought up with, and those that Jesus had told them as well.

Why, I imagine they must have thought, why do we have to wait?

And that is the question that we are still asking ourselves.

We also live in a liminal point. The kingdom is here, amongst us, and yet it is also yet to come.

Why are we still waiting for the coming of the kingdom? Why is the whole world not yet transformed by the glory of God into the creation that was originally intended? Indeed, as we look around, we could be forgiven for feeling that the state of creation is regressing, rather than advancing.

Paul, cast into prison with Silas, would undoubtedly have agreed. Why is everyone resisting the good news so hard.

Much of Paul’s theology revolves around demonstrating that Jesus is the Christ, the anointed Messiah, but that the consequence of that messianic revelation is not what he and the other Jews had expected it to be.

Because Paul focusses in on how Jesus’ death and resurrection have affected us, especially us Gentiles who are not part of God’s covenants with Abraham and Moses, because of his focus on the traditional western Christian themes of atonement and substitution, I feel we can have an unhelpful and possibly unhealthy concern about our personal salvation.

And yet Jesus says, in John’s words, ‘I ask not only on behalf of these (the disciples at the last supper, excluding Judas who has already left), not only on behalf of these, but also on behalf of those who believe in me through their word (that’s us), that they may all be one.’

And later – ‘The glory which you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one.’

So we are all in this together. God’s kingdom will be a community.

That isn’t to say that we will lose our individuality, but our individuality will be less important than our commonality. Not a message that chimes with 21st century western thought.

And God loves all of his creation, no matter how flawed and broken it is.

There can be a temptation to see this life as a time of trial, a test almost, that we have to pass in order to get into heaven.

But God never intending this world to be a test for us. He created the world good and whole, and made Adam and Eve to enjoy it in his own image and glory. The world was created to be enjoyed and cared for, by us. Not because God needed to create it, but because he chose to create it and us, and to share his love with us

That creation went wrong, and God seeks, through us, to repair and restore it.

Progressively he has sought to repair it, through his covenant with Noah, through his covenant with Abraham, and his covenant with Moses. Each time, we have proven to be more stubborn than God hoped we would be, and so creation has proved more difficult to fix.

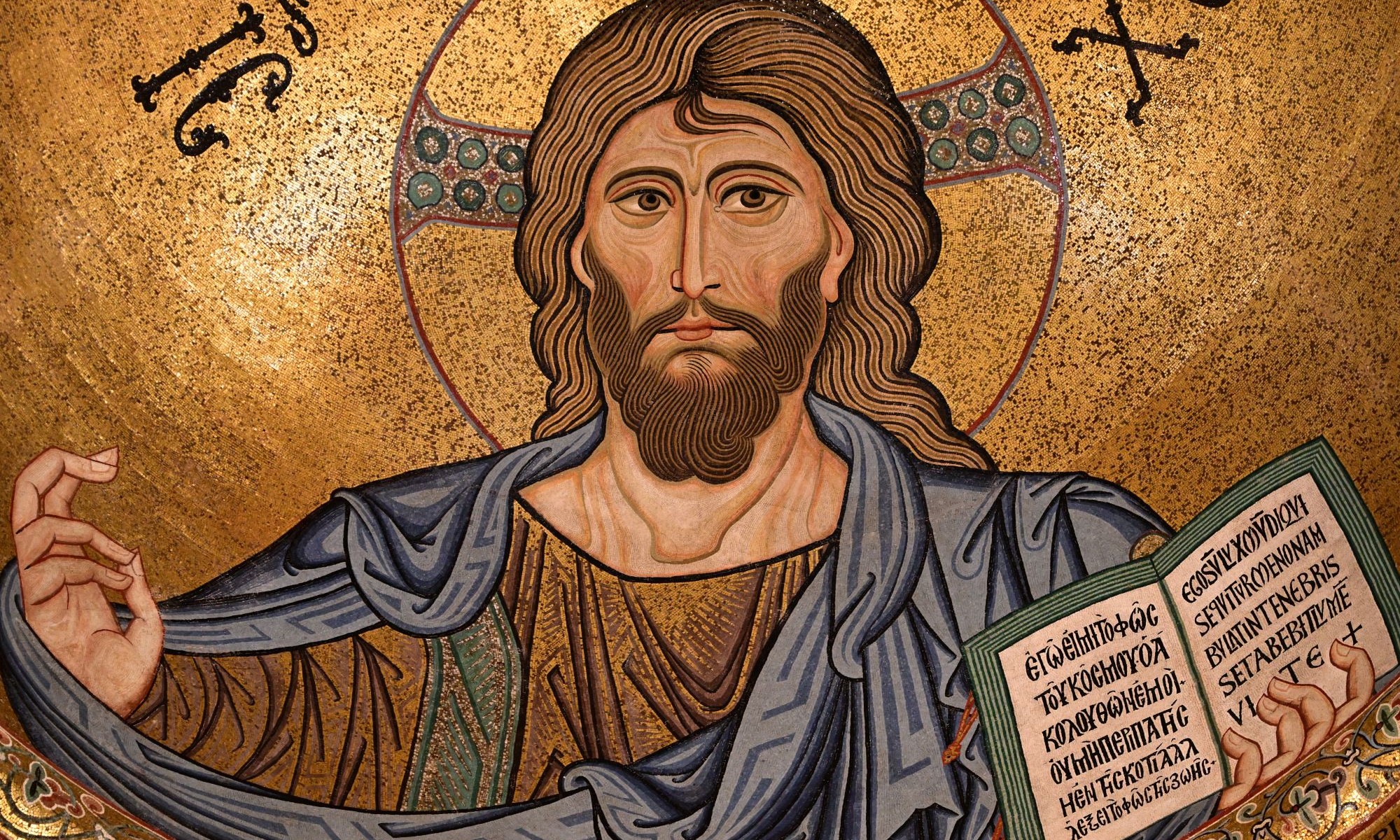

Finally, God played his trump card. He would himself intervene to save creation, by sending his Son to show us what the right creation looked like. In Jesus, we would be able to see the glory of God, and would know what we were originally called to be.

And in addition, Jesus would call in all the negativity of creation, all the darkest emotions of anger and hatred, let them do their worst on him, and then three days later, show that they had no power at all over God.

But showing that these forces of evil are powerless against God doesn’t make them go away. And there is still evil in the world, as we can see all around us.

These forces still have power over us, especially if we try to resist them in our own power, rather than trusting in God.

These powers throw Paul and Silas into jail.

It is characteristic of this liminal time that we live in, that they, like Peter on another occasion, escape, but many other apostles and Christians did not escape. Why are Peter and Paul saved, while James for example, is cast into prison and executed?

Why are nineteen innocent children killed by a deranged teenager in Texas? I say deranged, but is that the explanation? Speaking of evil isn’t very fashionable at the moment – we try to find reasons for things, excuses from childhood or upbringing. Nurture over nature. And certainly circumstances can cause us to be broken; can tempt us to do the wrong thing. Adam and Eve certainly discovered that. Their nature was good, but circumstances and others tempted them to do wrong. But even if it is all circumstances, we can still talk of evil pervading the world, even if it is of our own making.

But why is it there? Why create a creation with the capacity for wrong?

God doesn’t have to explain himself to us. It may be a miracle that recued Paul and Silas from prison, but it wasn’t a miracle that put them in prison. God didn’t beat and imprison them, we did in our pride and arrogance and self-indulgence. Yes, God permits us to be who we are, and we can ask other questions about why that is, but God does not compel us to be sinful. We do that to ourselves.

We, in a wide sense, permit our self-indulgence of wanting to own guns become more important to us than the Gospel message of caring for others. We may say that here, in this country, we don’t, but we are all one before God. We cannot just turn our backs on the sins and suffering of others. We are all in this together.

So the question is not why we are still in this liminal period of waiting for the fullness of the Kingdom of God.

We are still in this period because creation still needs to be remade, and God, who made us as the crowning glory of his creation, wants to glorify us yet further by making us part of the remaking of creation. Not in a narrow, you broke it, you own it way, but because he wants to reaffirm us as the image of God.

We are part of the problem, and part of the solution. Certainly not the whole solution – only God can show us what the true rightness of creation is, which he did in his Son.

So we do not know why we wait for the coming Kingdom, but we do know that it is also already here, in the person of Jesus Christ.

We do not know why we wait, but we do know that while we do, we are not passive observers, but active participants.

We do not know why we wait, but like the disciples, we wait in the knowledge that God so loved the world that he gave us his only Son. We know that the outcome is settled, the victory is won, the new creation will come.

Amen.